From the United Kingdom to a Celtic Union

Kevin Rejent • December 18, 2019

Does the British Election Make a Celtic Union of Northern Ireland, Scotland, and the Republic of Ireland More Likely?

When King George V surveyed his empire before World War I, he saw approximately one-quarter of the Earth’s land mass and people under his crown. The sun truly never set on the British Empire, and Pax Britannica had stabilized the world for several decades. But then history happened as nations sought to rule themselves and far-flung territories became more of a burden to rule than benefit to the empire. Over the next century, the United Kingdom shrunk from 13,700,000 square miles to 93,628 square miles, or .68% of its summit, and rules over .88% of the world’s population. Hong Kong was the most recent defection in 1997, leaving the United Kingdom with essentially its population base in the British Isles, a few strategic ports, and some nice Caribbean vacation spots.

This is not an effort to denigrate Great Britain as a has-been power clinging to relevance. It is still one of the world’s foremost military, economic, and cultural powers. This history is provided to demonstrate that time has a way of changing things, and “permanent” truths are subject to unforeseen events and forces even the most visionary leaders cannot control. And when perceived community interests diverge from those of the larger nation, division is sought and, sometimes, obtained. The United Kingdom may be approaching another such point after last week’s Parliament vote.

Last week’s vote leaves no doubt: Brexit will happen. And Boris Johnson, a man about whom we have written in the past, will be the person to pilot that ship out of the European Union. The certainty of the exit ends a period of volatility that has hampered British politics and business for several years, and certainty is good. However, the certainty of Brexit has unleashed related uncertainties that will plague the United Kingdom for the next decade or longer, potentially leading to a further contraction of Great Britain and, eventually, the forming of a rival firmly planted within the European Union.

Scotland

Scottish independence is not a new passion. The two neighbors have centuries of conflict and cooperation, and since the Treaty of Union merged the nations in 1707, Scottish nationalists have been clamoring for a reversal. Most recently in 2014, a referendum on independence resulted in a 55-45 vote to remain within the United Kingdom. But that was before the Brexit referendum. In that election, Scottish voters voices a strong desire to remain within the EU, only to be overruled by their British and Welsh countrymen.

In last week’s Parliamentary elections, the Scottish Nationalist Party, formed to promote an independent Scotland, won 48 of Scotland’s 59 seats in Parliament, 13 more seats than the previous election. Its percentage of the vote increased 8% to 45%. Leader Nicola Sturgeon has already asked Prime Minister Boris Johnson for a second referendum, which he has refused.

While there would seem to be movement towards independence, it should not be forgotten that, just five years ago, Scottish voters rejected leaving the UK by 10 percent. And the SNP’s 45 percent of the 2019 vote, while impressive, is the same percentage of those who voted for independence; thus it is unclear how much public opinion has shifted. Further, the electorate is likely exhausted with no appetite for another bruising campaign after the 2014 independence vote, 2016 Brexit vote, and 2017 and 2019 Parliamentary elections.

However, if Scottish nationalists are patient, Brexit may advance their cause far more effectively than any campaign. 62% of the voters in Scotland voted Remain. Further, Boris Johnson’s breed of Conservatism is often interpreted as English nationalist and paternalistic towards Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. He was forced to work with everyone prior to the election since he was leading a minority government; but now that he has a large Parliamentary majority composed almost exclusively of English members, he may pay less attention to the other nations within the Kingdom. Further, Brexit will harm the British economy, and leaving the UK to join the EU will become more appealing in time. If Scottish nationalists spend the next several years linking independence with EU membership (and a reversal of the difficulties Brexit will bring) and give the electorate time to get over the recent wave of monumental elections, another vote on an independent Scotland could occur within the next five to ten years.

Northern Ireland

More surprising than the SNP’s success in Scotland were the victories of Nationalist parties in Northern Ireland. For the first time in Northern Irish history, they won more seats than Loyalist parties, 10 to 8 (with one additional seat going to a compromise party). Additionally, Northern Ireland voted 56-44 to remain within the EU in the 2017 referendum. Northern Irish voters understand that, regardless of the extremely tumultuous religious conflicts within its nation and with the Republic of Ireland, its economy is intimately linked to that of the Republic, which requires it to be a member of the EU to continue unfettered trade.

The Brexit process has exposed deep cracks in the English-Northern Irish relationship, but the Conservatives’ need of the Democratic Unionist Party’s support to remain in power prior to the recent election meant that any plans needed to meet with the approval of at least some Northern Irish leaders. Mr. Johnson, like his predecessor Theresa May, was consistently flabbergasted that the EU did not disregard the interests of Ireland during Brexit negotiations, but were unable to disregard their own Irish’s considerations since they were needed to govern. With his large England-based majority, Mr. Johnson is free from those shackles. On the most perplexing issues of the negotiations, such as customs complications and a backstop to EU regulations, Mr. Johnson has already shown himself to be more concerned with getting a deal than finding solutions that benefit Northern Ireland. As the EU exercises tougher negotiation tactics (since it will be negotiating with a third party instead of a member state), the UK will find itself with less and less leverage, and Northern Irish interests are politically the easiest for Mr. Johnson to disregard. With it already being the nation absorbing the largest blow from Brexit, the lack of concern from Westminster might be enough to soften some Unionist positions.

Of course, *might* is the operative word here. Centuries of conflict followed by several decades of violence are not swept away simply because one side wants access to markets for their widgets. The Good Friday Accords have greatly improved relations between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and common EU membership has provided a neutral setting for the nations to jointly prosper. But removing EU membership does not mean that the parties will be drawn together in common cause and Northern Ireland will abandon the United Kingdom.

What About Wales?

Recent polling puts support for Welsh independence at around 30%. Additionally, Wales voted in favor of Brexit. Wales is comfortable within the UK, and the nations of the potential future Celtic Union should not waste energy attempting to extract it from the Kingdom.

Toward a Celtic Union

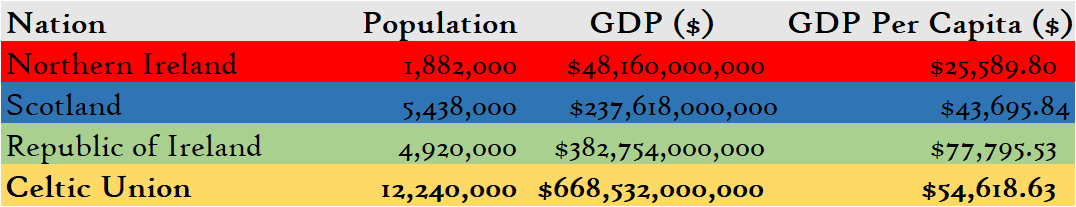

On paper, a Celtic Union of Scotland, Ireland, and Northern Ireland makes perfect sense. The three nations are much more culturally similar to each other than England, economically invested in the EU, and Northern Ireland and Scotland would be able to exert more control over their national affairs. It would form the world’s 21st largest economy, and its GDP per capita would fit between Sweden and the Netherlands.

This is not an effort to denigrate Great Britain as a has-been power clinging to relevance. It is still one of the world’s foremost military, economic, and cultural powers. This history is provided to demonstrate that time has a way of changing things, and “permanent” truths are subject to unforeseen events and forces even the most visionary leaders cannot control. And when perceived community interests diverge from those of the larger nation, division is sought and, sometimes, obtained. The United Kingdom may be approaching another such point after last week’s Parliament vote.

Last week’s vote leaves no doubt: Brexit will happen. And Boris Johnson, a man about whom we have written in the past, will be the person to pilot that ship out of the European Union. The certainty of the exit ends a period of volatility that has hampered British politics and business for several years, and certainty is good. However, the certainty of Brexit has unleashed related uncertainties that will plague the United Kingdom for the next decade or longer, potentially leading to a further contraction of Great Britain and, eventually, the forming of a rival firmly planted within the European Union.

Scotland

Scottish independence is not a new passion. The two neighbors have centuries of conflict and cooperation, and since the Treaty of Union merged the nations in 1707, Scottish nationalists have been clamoring for a reversal. Most recently in 2014, a referendum on independence resulted in a 55-45 vote to remain within the United Kingdom. But that was before the Brexit referendum. In that election, Scottish voters voices a strong desire to remain within the EU, only to be overruled by their British and Welsh countrymen.

In last week’s Parliamentary elections, the Scottish Nationalist Party, formed to promote an independent Scotland, won 48 of Scotland’s 59 seats in Parliament, 13 more seats than the previous election. Its percentage of the vote increased 8% to 45%. Leader Nicola Sturgeon has already asked Prime Minister Boris Johnson for a second referendum, which he has refused.

While there would seem to be movement towards independence, it should not be forgotten that, just five years ago, Scottish voters rejected leaving the UK by 10 percent. And the SNP’s 45 percent of the 2019 vote, while impressive, is the same percentage of those who voted for independence; thus it is unclear how much public opinion has shifted. Further, the electorate is likely exhausted with no appetite for another bruising campaign after the 2014 independence vote, 2016 Brexit vote, and 2017 and 2019 Parliamentary elections.

However, if Scottish nationalists are patient, Brexit may advance their cause far more effectively than any campaign. 62% of the voters in Scotland voted Remain. Further, Boris Johnson’s breed of Conservatism is often interpreted as English nationalist and paternalistic towards Scotland, Northern Ireland, and Wales. He was forced to work with everyone prior to the election since he was leading a minority government; but now that he has a large Parliamentary majority composed almost exclusively of English members, he may pay less attention to the other nations within the Kingdom. Further, Brexit will harm the British economy, and leaving the UK to join the EU will become more appealing in time. If Scottish nationalists spend the next several years linking independence with EU membership (and a reversal of the difficulties Brexit will bring) and give the electorate time to get over the recent wave of monumental elections, another vote on an independent Scotland could occur within the next five to ten years.

Northern Ireland

More surprising than the SNP’s success in Scotland were the victories of Nationalist parties in Northern Ireland. For the first time in Northern Irish history, they won more seats than Loyalist parties, 10 to 8 (with one additional seat going to a compromise party). Additionally, Northern Ireland voted 56-44 to remain within the EU in the 2017 referendum. Northern Irish voters understand that, regardless of the extremely tumultuous religious conflicts within its nation and with the Republic of Ireland, its economy is intimately linked to that of the Republic, which requires it to be a member of the EU to continue unfettered trade.

The Brexit process has exposed deep cracks in the English-Northern Irish relationship, but the Conservatives’ need of the Democratic Unionist Party’s support to remain in power prior to the recent election meant that any plans needed to meet with the approval of at least some Northern Irish leaders. Mr. Johnson, like his predecessor Theresa May, was consistently flabbergasted that the EU did not disregard the interests of Ireland during Brexit negotiations, but were unable to disregard their own Irish’s considerations since they were needed to govern. With his large England-based majority, Mr. Johnson is free from those shackles. On the most perplexing issues of the negotiations, such as customs complications and a backstop to EU regulations, Mr. Johnson has already shown himself to be more concerned with getting a deal than finding solutions that benefit Northern Ireland. As the EU exercises tougher negotiation tactics (since it will be negotiating with a third party instead of a member state), the UK will find itself with less and less leverage, and Northern Irish interests are politically the easiest for Mr. Johnson to disregard. With it already being the nation absorbing the largest blow from Brexit, the lack of concern from Westminster might be enough to soften some Unionist positions.

Of course, *might* is the operative word here. Centuries of conflict followed by several decades of violence are not swept away simply because one side wants access to markets for their widgets. The Good Friday Accords have greatly improved relations between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, and common EU membership has provided a neutral setting for the nations to jointly prosper. But removing EU membership does not mean that the parties will be drawn together in common cause and Northern Ireland will abandon the United Kingdom.

What About Wales?

Recent polling puts support for Welsh independence at around 30%. Additionally, Wales voted in favor of Brexit. Wales is comfortable within the UK, and the nations of the potential future Celtic Union should not waste energy attempting to extract it from the Kingdom.

Toward a Celtic Union

On paper, a Celtic Union of Scotland, Ireland, and Northern Ireland makes perfect sense. The three nations are much more culturally similar to each other than England, economically invested in the EU, and Northern Ireland and Scotland would be able to exert more control over their national affairs. It would form the world’s 21st largest economy, and its GDP per capita would fit between Sweden and the Netherlands.

However, if the stars were to ever align for this Union, it would be because all parties exhibited patience and perfect statecraft. Scotland would likely be the first domino to fall. With an already active independence movement, a strong desire to remain within the EU, and North Sea oil revenue to ease the transition, the Scottish could conceivably vote for independence in five to ten years. It would then face the problems Northern Ireland is dealing with now related to borders and customs checks. Further, the EU might not be willing to discuss membership until Scotland is independent, thus making the Scotleave transition potentially as calamitous as Brexit.

If Scotland were to leave, Northern Ireland would then look around and recognize that it is even more of a cultural and geographic mismatch with the United Kingdom than before. However, it is likely too small and not economically prosperous enough to consider independence. Despite the temptation of pushing for the union of Northern Ireland and the Republic, the Republic would be wise to let Northern Ireland find its proper place without pressure. It is quite conceivable that Northern Ireland will feel most comfortable sticking with Scotland. And if Scotland has been granted EU membership, the problems of controls between the Republic and Northern Ireland would be solved.

But what if Scotland is not immediately granted EU membership and access to the Common Market? Would it be worth seeking independence? Would Northern Ireland follow? If Ireland is savvy (and its current leadership is very talented), it will work with the EU to steer Scotland towards a loose union with Ireland. The nations would have a limited “national” government, but essentially remain separate nations, as the Scots would prefer it status within the UK to be. As noted above, Northern Ireland might be reluctant to join the Republic of Ireland; but if it could also maintain autonomy within this Union, and Scotland and the Republic could entice it with investment at or above the UK’s current investments, Northern Ireland might also jump.

What Would the Celtic Union Look Like?

Scotland and Northern Ireland would likely only leave the UK for more autonomy and EU market access. Thus, the Celtic Union would have to operate through a weak central government that handles mostly EU affairs with remaining powers reverting to the member states. The head of the central government could be rotated between the states (yes, even though Northern Ireland is much weaker – Scotland and the Republic would essentially be overpaying for its membership), and each state could be in charge of certain ministries, which would also be rotated. The Union would only have one vote in the European Council, but with the EU’s ninth largest population and sixth largest economy, it could have a great impact on European debates. The cultural issues within Northern Ireland and between the North and the Republic of Ireland would not disappear; but having protestant Scotland as a friend to both sides could provide current protestant Unionists some comfort.

Is the Celtic Union Inevitable?

Immediately after last week’s election, commentators rushed in front of cameras to pronounce that Scottish independence is now inevitable. They are wrong. It is more likely now; but the political, cultural, and economic foundations keeping Scotland within the United Kingdom run deeper than Brexit, as do those tying Belfast to London.

However, if the Johnson government promotes English nationalism and ignores the needs of the other nations within the Kingdom, independence looks a slightly more attractive. And if Scotland and Northern Ireland can fast-track their reentry into the EU through a loose union with the Republic of Ireland, it looks more attractive still. Slowly, over the course of several years, there are many opportunities for Scotland and Northern Ireland the drift away from the United Kingdom as so many other nations have done before them. Unless the Great Britain recognizes this possibility and actively demonstrates that it is not taking their relationships for granted, the contraction of the United Kingdom might continue, and the rise of a Celtic Union may begin.

If Scotland were to leave, Northern Ireland would then look around and recognize that it is even more of a cultural and geographic mismatch with the United Kingdom than before. However, it is likely too small and not economically prosperous enough to consider independence. Despite the temptation of pushing for the union of Northern Ireland and the Republic, the Republic would be wise to let Northern Ireland find its proper place without pressure. It is quite conceivable that Northern Ireland will feel most comfortable sticking with Scotland. And if Scotland has been granted EU membership, the problems of controls between the Republic and Northern Ireland would be solved.

But what if Scotland is not immediately granted EU membership and access to the Common Market? Would it be worth seeking independence? Would Northern Ireland follow? If Ireland is savvy (and its current leadership is very talented), it will work with the EU to steer Scotland towards a loose union with Ireland. The nations would have a limited “national” government, but essentially remain separate nations, as the Scots would prefer it status within the UK to be. As noted above, Northern Ireland might be reluctant to join the Republic of Ireland; but if it could also maintain autonomy within this Union, and Scotland and the Republic could entice it with investment at or above the UK’s current investments, Northern Ireland might also jump.

What Would the Celtic Union Look Like?

Scotland and Northern Ireland would likely only leave the UK for more autonomy and EU market access. Thus, the Celtic Union would have to operate through a weak central government that handles mostly EU affairs with remaining powers reverting to the member states. The head of the central government could be rotated between the states (yes, even though Northern Ireland is much weaker – Scotland and the Republic would essentially be overpaying for its membership), and each state could be in charge of certain ministries, which would also be rotated. The Union would only have one vote in the European Council, but with the EU’s ninth largest population and sixth largest economy, it could have a great impact on European debates. The cultural issues within Northern Ireland and between the North and the Republic of Ireland would not disappear; but having protestant Scotland as a friend to both sides could provide current protestant Unionists some comfort.

Is the Celtic Union Inevitable?

Immediately after last week’s election, commentators rushed in front of cameras to pronounce that Scottish independence is now inevitable. They are wrong. It is more likely now; but the political, cultural, and economic foundations keeping Scotland within the United Kingdom run deeper than Brexit, as do those tying Belfast to London.

However, if the Johnson government promotes English nationalism and ignores the needs of the other nations within the Kingdom, independence looks a slightly more attractive. And if Scotland and Northern Ireland can fast-track their reentry into the EU through a loose union with the Republic of Ireland, it looks more attractive still. Slowly, over the course of several years, there are many opportunities for Scotland and Northern Ireland the drift away from the United Kingdom as so many other nations have done before them. Unless the Great Britain recognizes this possibility and actively demonstrates that it is not taking their relationships for granted, the contraction of the United Kingdom might continue, and the rise of a Celtic Union may begin.