The Future of the Euro (or Lack Thereof)

Kevin Rejent • May 20, 2020

Covid-19 is exposing deep cracks within the Eurozone. Can the divide be bridged?

*This article is best viewed in its PDF format, which is available here.*

Executive Summary

The COVID-19 crisis has laid bare disagreements in the Eurozone regarding nations’ obligations to each other as the continent contemplates the enormous task of economic recovery. Old prejudices in the north developed when southern nations were more fiscally reckless than they are at present have tied the hands of politicians on both sides of the divide. The hardest-hit nations, Italy and Spain, are seeking a joint recovery effort while fiscally prudent nations such as the Netherlands and Germany believe loans to impacted areas are sufficient. Despite token gestures and speeches praising European unity, the great divide remains.In this article, we look at the issue through the eyes of two nations that best represent the views of their respective “side” of the discussion: The Netherlands and Italy. Divergent economic and cultural priorities have resulted in prejudices and resentment between the populations which must be manifested in the actions of politicians if the politicians wish to remain in power. Without the political ability to overcome these positions, the Euro could be in trouble.

The most likely course for the Euro is to continue some version of the status quo. The members would patch over their differences and hope resentment would die down in the post-COVID era. However, this “easiest” path poses plenty of issues for the fiscally prudent northern nations since the trajectory of European institutions is almost always towards further integration, and potential new Eurozone members much more closely resemble the zone’s southern members. A less likely, but still possible, scenario sees politics in Italy causing it to go down an unfortunate path of reintroducing the Lira as a parallel currency and eventually redenominating its debt. In this scenario, Greece might also leave the Eurozone, but with the assistance of the remaining Eurozone members. A final scenario sees the Euro broken into three regional Euros under the auspices of the ECB. While this is also unlikely, it would solve some political issues and leave little doubt that the regional Euros meet the requirements of an Optimum Currency Area.

The Promise of Europe

As they met on Capitoline Hill to sign the Treaty of Rome in 1957, the leaders of Italy, France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and West Germany dreamed of a cooperative Europe where continental advancement triumphed over petty national gain. These nations were joined thirty-five years later by six others in Maastricht, Netherlands to bind monetary policy through the Euro. Since then, sixteen more European nations have joined the EU (with the UK subsequently leaving), and nineteen nations now belong to the Eurozone. But now, the nations that hosted the signing of the treaties upon which the great European experiment is based, Italy and the Netherlands, embody the continental disagreements on the EU and the Euro that the current COVID-19 crisis has laid bare…disagreements that just may lead to the end of the Euro.

It is hard to imagine a world without the Euro, since most level-headed analyst would agree it has been a rousing success. However, it has only been in use for eighteen years, and several of those were spent handling crises in specific nations or Eurozone-wide. But handle them it has, and history will judge the actions of the European Central Bank kindly, or at least neutrally. Of course, it will never satisfy everyone, and hindsight provides plenty of hiccups, but overall, the ECB has been a force for good in Europe. It should continue to play a central role in the European economy, regardless of the paths taken by member states in the post-COVID future.

Recent European History

(like…past few months recent)

(like…past few months recent)

With the spread of COVID-19 and subsequent economic crash, European nations have been forced to consider both national and continental responses to achieve the most effective recovery. While there have been some incredible shows of pan-European unity, the crisis has also accelerated and deepened intra-continental divides and tested the strength of institutions. The fact that Italy and Spain, two frequent targets of fiscally prudent northern Europeans’ derision, were the first and hardest hit on the continent only complicated matters.

When the virus first hit northern Italy, there was some confidence that it could be contained quickly and not cause much disruption outside of the initially impacted regions Lombardy and Veneto. But it crept out of those areas and, within a few weeks, forced Italy to lock its citizens into their homes and basically shut down the economy. Other nations, initially Spain and then France, followed, and the pandemic was now continent-wide and spreading fast.

The ECB wobbled in its first COVID-19 test, with President Christine Lagarde first stating that the role of the ECB was not to minimize the bond spread between nations. This caused Italian borrowing costs to shoot up as investors feared the ECB would not come to Italy’s aid. Lagarde quickly realized the errors of her statement and leapt into action to defend Italy and other nations whose bonds were under pressure. Eventually, the ECB implemented a bond-purchasing program of over $750B, and even started buying non-sovereign bonds, which is similar to the US Federal Reserve’s actions (although on a smaller scale). So thus far, the EBC has done its best to stabilize the Eurozone and provide the monetary foundation for recovery.

In the US, there has also been a multi-trillion-dollar fiscal response to avoid the worst-case scenarios and position the nation for recovery. Europe obviously needs something similar, as the individual nations are not, with a few exceptions, capable of raising the amount of money that will be needed to keep their people fed and working while digging out of the crater left by COVID-19. The first suggestion was the oft-discussed Eurobonds, which would create an attractive new vehicle to mutualize some portion of European debt. The northern nations could not be more opposed to this, and that idea was quickly replaced by a proposal to issue limited-time bonds specifically to aid in recovery: Coronabonds. Once again, however, northern nations shot down this idea as edging too close to the mutualization line. Then Spain devised a popular compromise solution that paid for recovery out of future EU budgets instead of debt obligations. This has also stalled, as northern nations would rather promote a package, including loans with strings attached, that is completely unacceptable to the countries in need. Therefore, the EU response has been nothing but solemn talk and unfulfilled potential.

What Does This Have to do With the Euro?

When evaluating the overlapping European structures, mischievous situations that were certainly not contemplated by their architects come into focus. And while exploiting these cracks in the system would be dangerous, a desperate nation that perceives that it has been abandoned by its fellow Europeans just may take that chance.

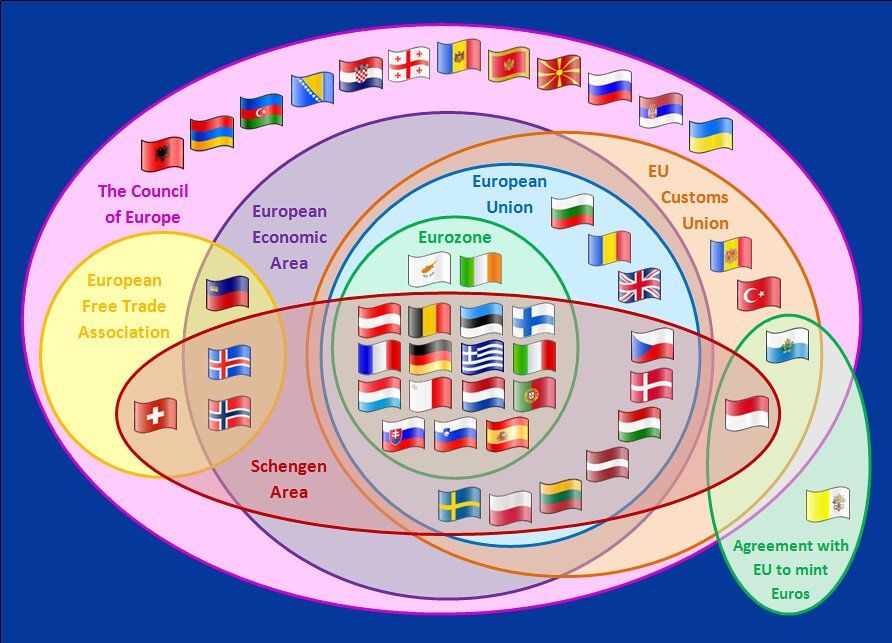

As this Venn diagram from the European Council on Foreign Relations demonstrates, Europe is a jumble of institutions and agreements.

A nation can be a member of several European institutions without being required to join others. There are currently nine members of the European Union that are not members of the Eurozone, and four members of the EU Customs Union that are not even members of the EU. While sliding between these groups is challenging and has generally been in the direction of more integration, theoretically one could go the other way.

These institutions craft policy to varying degrees of integration, but none are more impactful than the ECB crafting of monetary policy for the nineteen Eurozone members. The system is based upon the work of Nobel Prize winner Robert Mundell on Optimum Currency Areas, or geographic areas that would most benefit from sharing a currency, regardless of national borders. According to Dr. Mundell, there are four criteria for an optimum currency area:

1. A large, available, and integrated labor market which allows workers to move freely throughout the area and smooth out unemployment in any single zone.

2. The flexibility of pricing and wages, along with the mobility of capital, to eliminate regional trade imbalances.

3. A centralized budget or control to redistribute wealth to parts of the area which suffer due to labor and capital mobility.

4. Similar business cycles in the participating regions and timing for economic data to avoid a shock in any one area.

Criteria 1 and 2 are mostly satisfied by the wider European Union’s mandate of free movement of people, capital, and goods between member states. Criterion 3 is somewhat satisfied by the EU, with supplements to member state budgets to promote economic harmony, but is also often a primary issue of concern in the Eurozone. Criterion 4 is more theoretical, and thus the easiest upon which to craft arguments for or against the Euro as an Optimum Currency Area. But it is important to note that the Euro is managed by the ECB, which only controls monetary policy. Fiscal policy is left to the individual nations. Thus, the monetary policy of one Eurozone nation is directly impacted by the fiscal policy of another. Herein lies the crux of virtually every Eurozone disagreement this century.

Further fiscal integration is often discussed as the next step in European integration, with Mario Draghi campaigning for it in his final speech as ECB President. Despite the appearance of momentum for this idea pre-COVID, a deeper look indicates further integration was unlikely then and even more unlikely now. While the UK was never in the Eurozone, its issues with deeper European political integration and loss of sovereignty made Brexit inevitable. This concern for sovereignty is not contained to the west side of the English Channel. Eurosceptics are sizable blocks in most nations and their ranks would swell if citizens saw their countries run more and more by European entities. For example, the Gilets Jaune protests are an example of citizens opposing the actions of their own government. How much more intense would the protests be if they were protesting actions imposed upon them by European central bankers? For these and many more reasons, deeper fiscal integration of the Eurozone economies is unlikely, and Europe is stuck navigating the COVID-19 crisis under current institutional constraints.

While the current institutions have done some things well, rifts have existed from the beginning, and the long process of fracturing has accelerated in the current crisis. Historically, northern European nations such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, Austria, and Finland have taken southern European nations such as Italy, Greece, and Spain to task for irresponsible spending, and they’ve often had good reason. However, since the financial crisis of 2008-10, these nations have been pretty responsible, and their budget deficits have been consistently improving. Most of these nations are actually running surpluses when debt service is removed.

But Europe’s current financial malaise has nothing to do with reckless spending in southern Europe, nor can it be solved by northern European frugality. It is the result of a calamity that knows no borders and is not any European nation’s “fault.” So why the hesitation to fight the economic impact together, which would absolutely benefit everyone? Politically, the Dutch and Luxembourgian and, to some extent German, electorate are deeply suspicious of southern Europe, and being seen as “giving in” to their requests for money can be politically costly. At the same time, voters in southern nations question the value of a union with “partners” who constantly lecture them about prudence while stacking the deck against their growth through either aggressive tax competition (Netherlands or Luxembourg) or trade practices (Germany). Viewing the political, economic, and social issues through Dutch and Italian eyes clarifies the conflict and provides insight regarding why the Euro is in a precarious position.

The Dutch Position

Former Eurogroup President and Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem made headlines (negative abroad but wildly positive at home) when he said about southern countries’ indebtedness, “you can’t first spend all your money on drinks and women, and subsequently ask for financial support.” This view was long held but rarely spoken, and is the view of a large share of the Dutch electorate.

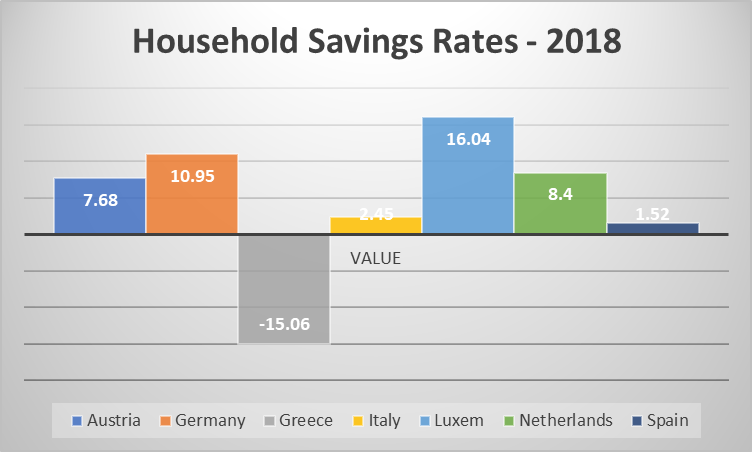

Since this is the popular view in the Netherlands, politicians are constrained to act in accordance with this belief. To be seen as acceding to southern needs would be viewed as selling out Dutch pensioners for undisciplined spendthrifts. And this opinion is not without some basis in truth. The Netherlands, along with Germany, Luxembourg, and Austria, have much higher net national savings rates than Italy, Greece, and Spain. The Dutch value financial constraint over immediate quality of life experiences, and do not believe the citizens of southern nations work hard enough or appropriately value saving for the future.

These institutions craft policy to varying degrees of integration, but none are more impactful than the ECB crafting of monetary policy for the nineteen Eurozone members. The system is based upon the work of Nobel Prize winner Robert Mundell on Optimum Currency Areas, or geographic areas that would most benefit from sharing a currency, regardless of national borders. According to Dr. Mundell, there are four criteria for an optimum currency area:

1. A large, available, and integrated labor market which allows workers to move freely throughout the area and smooth out unemployment in any single zone.

2. The flexibility of pricing and wages, along with the mobility of capital, to eliminate regional trade imbalances.

3. A centralized budget or control to redistribute wealth to parts of the area which suffer due to labor and capital mobility.

4. Similar business cycles in the participating regions and timing for economic data to avoid a shock in any one area.

Criteria 1 and 2 are mostly satisfied by the wider European Union’s mandate of free movement of people, capital, and goods between member states. Criterion 3 is somewhat satisfied by the EU, with supplements to member state budgets to promote economic harmony, but is also often a primary issue of concern in the Eurozone. Criterion 4 is more theoretical, and thus the easiest upon which to craft arguments for or against the Euro as an Optimum Currency Area. But it is important to note that the Euro is managed by the ECB, which only controls monetary policy. Fiscal policy is left to the individual nations. Thus, the monetary policy of one Eurozone nation is directly impacted by the fiscal policy of another. Herein lies the crux of virtually every Eurozone disagreement this century.

Further fiscal integration is often discussed as the next step in European integration, with Mario Draghi campaigning for it in his final speech as ECB President. Despite the appearance of momentum for this idea pre-COVID, a deeper look indicates further integration was unlikely then and even more unlikely now. While the UK was never in the Eurozone, its issues with deeper European political integration and loss of sovereignty made Brexit inevitable. This concern for sovereignty is not contained to the west side of the English Channel. Eurosceptics are sizable blocks in most nations and their ranks would swell if citizens saw their countries run more and more by European entities. For example, the Gilets Jaune protests are an example of citizens opposing the actions of their own government. How much more intense would the protests be if they were protesting actions imposed upon them by European central bankers? For these and many more reasons, deeper fiscal integration of the Eurozone economies is unlikely, and Europe is stuck navigating the COVID-19 crisis under current institutional constraints.

The Rift

While the current institutions have done some things well, rifts have existed from the beginning, and the long process of fracturing has accelerated in the current crisis. Historically, northern European nations such as the Netherlands, Luxembourg, Germany, Austria, and Finland have taken southern European nations such as Italy, Greece, and Spain to task for irresponsible spending, and they’ve often had good reason. However, since the financial crisis of 2008-10, these nations have been pretty responsible, and their budget deficits have been consistently improving. Most of these nations are actually running surpluses when debt service is removed.

But Europe’s current financial malaise has nothing to do with reckless spending in southern Europe, nor can it be solved by northern European frugality. It is the result of a calamity that knows no borders and is not any European nation’s “fault.” So why the hesitation to fight the economic impact together, which would absolutely benefit everyone? Politically, the Dutch and Luxembourgian and, to some extent German, electorate are deeply suspicious of southern Europe, and being seen as “giving in” to their requests for money can be politically costly. At the same time, voters in southern nations question the value of a union with “partners” who constantly lecture them about prudence while stacking the deck against their growth through either aggressive tax competition (Netherlands or Luxembourg) or trade practices (Germany). Viewing the political, economic, and social issues through Dutch and Italian eyes clarifies the conflict and provides insight regarding why the Euro is in a precarious position.

The Dutch Position

Former Eurogroup President and Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem made headlines (negative abroad but wildly positive at home) when he said about southern countries’ indebtedness, “you can’t first spend all your money on drinks and women, and subsequently ask for financial support.” This view was long held but rarely spoken, and is the view of a large share of the Dutch electorate.

Since this is the popular view in the Netherlands, politicians are constrained to act in accordance with this belief. To be seen as acceding to southern needs would be viewed as selling out Dutch pensioners for undisciplined spendthrifts. And this opinion is not without some basis in truth. The Netherlands, along with Germany, Luxembourg, and Austria, have much higher net national savings rates than Italy, Greece, and Spain. The Dutch value financial constraint over immediate quality of life experiences, and do not believe the citizens of southern nations work hard enough or appropriately value saving for the future.

Politicians that may disagree with this sentiment cannot express that disagreement if they want to remain in office. Great policy ideas do not benefit anyone if their champions are not in office to implement them. And historically, Dutch domestic financial concerns take precedent over European harmony, so placing European well-being ahead of Dutch priorities is a politically dangerous path.

With a general election scheduled for March 2021, and potentially earlier if snap elections are called, Prime Minister Mark Rutte cannot afford to be seen as giving away Dutch financial stability in the middle of a global crisis. The far-right PVV and FvD are threats to his VVD-led coalition, and would pounce on any action that could be twisted into a pro-southern Europe giveaway by Dutch leaders. So while it is easy to suggest he stand up for the nation’s European brethren and convince his people to deepen integration, Mr. Rutte and his government must walk the tightrope between doing what they believe is best and what will allow them to remain in power (and thus allow them to continue to do what they view as good for several more years.)

The Dutch want to be a key player in European institutions. They do not want European institutions to cost them any more than the Dutch view them as currently costing. Thus, the Dutch will not take steps to leave the Euro, but their mindset, as demonstrated in their policy positions, may just drive other nations out.

The Italian Position

The Italian perspective is shaped by a prevailing view that its Eurozone partners treat it as a problem to be managed instead of with the level of respect that the third-largest economy in the group deserves. Italians resent the view that they are shirking work and partying the piazzas all night. They are well-aware of the nation’s economic history and also keenly aware of how challenging it is to dig out, especially when “partners” engage in actions some view as economic sabotage. Most Italians understand the value of EU and Eurozone membership, but feel underappreciated and frustrated by paternalistic treatment from northerners.

Italy is currently the third-largest economy in the European Union and the Eurozone. Thus, it contributes more to the ECB than all nations but Germany and France, and is far and away a net contributor to the European Union. Additionally, Italy and other southern nations bear the brunt of Europe’s biggest crisis pre-COVID: migration. In 2017, Italy spent €3.2B on increased naval activity and care of refugees that landed on its shores. Despite EU promises to share the burden financially and disperse refugees throughout the Union, Italy has received less that €1B in support from the EU for the care of migrants since 2015, and other nations (except Germany) have been slow to accept new refugees from the southern countries.

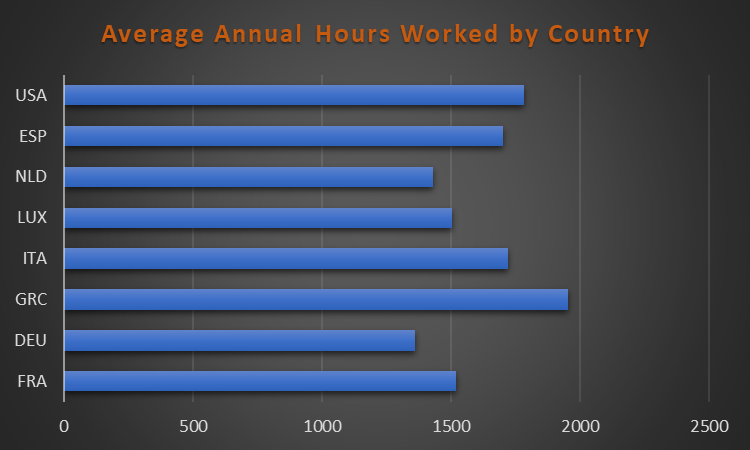

Despite being one of the largest contributors to the EU and ECB and shouldering more than its share of the refugee burden for the EU, Mr. Dijsselbloem’s attitude that Italians are spending their money on vices is hard to shake. Sure, bad decisions such as the “Baby Pensioni” arrangement that allowed government workers to retire with full lifetime pensions in their 30s and 40s needed to be corrected and have left a costly legacy. But Italian governments since the financial crisis have reigned in spending and attempted to reform labor laws to permit more employer flexibility. And Italian workers are not idle. In fact, they work quite a bit: fourth most hours in the Eurozone at 1,723 per year. This is behind leader Greece’s 1956, but well ahead of the 1,433 hours worker by the average Dutch worker per year and 1,363 worked by an average German.

With a general election scheduled for March 2021, and potentially earlier if snap elections are called, Prime Minister Mark Rutte cannot afford to be seen as giving away Dutch financial stability in the middle of a global crisis. The far-right PVV and FvD are threats to his VVD-led coalition, and would pounce on any action that could be twisted into a pro-southern Europe giveaway by Dutch leaders. So while it is easy to suggest he stand up for the nation’s European brethren and convince his people to deepen integration, Mr. Rutte and his government must walk the tightrope between doing what they believe is best and what will allow them to remain in power (and thus allow them to continue to do what they view as good for several more years.)

The Dutch want to be a key player in European institutions. They do not want European institutions to cost them any more than the Dutch view them as currently costing. Thus, the Dutch will not take steps to leave the Euro, but their mindset, as demonstrated in their policy positions, may just drive other nations out.

The Italian Position

The Italian perspective is shaped by a prevailing view that its Eurozone partners treat it as a problem to be managed instead of with the level of respect that the third-largest economy in the group deserves. Italians resent the view that they are shirking work and partying the piazzas all night. They are well-aware of the nation’s economic history and also keenly aware of how challenging it is to dig out, especially when “partners” engage in actions some view as economic sabotage. Most Italians understand the value of EU and Eurozone membership, but feel underappreciated and frustrated by paternalistic treatment from northerners.

Italy is currently the third-largest economy in the European Union and the Eurozone. Thus, it contributes more to the ECB than all nations but Germany and France, and is far and away a net contributor to the European Union. Additionally, Italy and other southern nations bear the brunt of Europe’s biggest crisis pre-COVID: migration. In 2017, Italy spent €3.2B on increased naval activity and care of refugees that landed on its shores. Despite EU promises to share the burden financially and disperse refugees throughout the Union, Italy has received less that €1B in support from the EU for the care of migrants since 2015, and other nations (except Germany) have been slow to accept new refugees from the southern countries.

Despite being one of the largest contributors to the EU and ECB and shouldering more than its share of the refugee burden for the EU, Mr. Dijsselbloem’s attitude that Italians are spending their money on vices is hard to shake. Sure, bad decisions such as the “Baby Pensioni” arrangement that allowed government workers to retire with full lifetime pensions in their 30s and 40s needed to be corrected and have left a costly legacy. But Italian governments since the financial crisis have reigned in spending and attempted to reform labor laws to permit more employer flexibility. And Italian workers are not idle. In fact, they work quite a bit: fourth most hours in the Eurozone at 1,723 per year. This is behind leader Greece’s 1956, but well ahead of the 1,433 hours worker by the average Dutch worker per year and 1,363 worked by an average German.

Hours worked is not necessarily the best gauge of productivity, however, as the efficiency of workers in the different nations and type of work they are performing are vital components. German manufacturing is among the most technologically advanced and efficient in the world, and the well-educated German workforce creates incredible products for sale throughout Europe and beyond. These sales create a large trade surplus, meaning the Germans are causing their trading partners to go into debt. Many Europeans believe their unwillingness to adjust the trade strategy violates the spirit, if not the letter, of EU and ECB agreements.

Similarly, Italians and other Europeans refuse to listen to northern European lectures on public debt when those nations’ tax structures greatly contribute to the southern nations’ need to take on debt. The Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Ireland, with a combined 4.4% of the EU’s population, house more than 50% of global foreign direct investment. This is often in the form of holding companies to exploit the favorable tax regimes and corporate law in these three nations. Italian companies will domicile in the Netherlands and pay corporate taxes there while performing almost all operations in Italy. Even former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi has moved the “headquarters” of his Mediaset empire from Milan to Amsterdam. Thus, the tax haven nations receive the lower corporate taxes but need to provide virtually no services to the taxpayer, while the nations that must provide services to the employees of those taxpayers are left without the tax revenue they should have to provide them.

It is often challenging to measure the strength of these opinions, and even harder to determine how citizens would like to act upon the opinions if given the opportunity. Fortunately, Davide Angelucci and Vincenzo Emanuele recently conducted a detailed survey of Italian attitudes towards to EU for Centro Italiano Studi Electtorali. According to the survey, a shocking 85% believe the EU is not helping Italy in its fight against COVID-19. 42% of Italians have a negative opinion of the EU, 23% are neutral, and only 35% hold positive opinion of the EU. Additionally, 35% would like to leave the EU, 18% prefer to leave the Euro but not the EU, and 47% would choose to stay in the EU. Anti-EU sentiment in Italy is growing, and failure of the EU and ECB to support Italy in near future could push it out of the Euro.

When considering how these divides might impact the Euro, it is important to begin any analysis with an understanding that *nobody* who would experience real consequences, financial or electoral, wants even a partial failure of the Euro. Of course, populist politicians like Matteo Salvini rattle sabers because 65% of the voters for his Lega party would like to leave the EU; but the financial and industrial giants in Lega’s northern Italian strongholds would certainly do all they could to kill any Italeave movement. So there is a strong desire to patch over any differences and retain the status quo. But disagreements occur, intentions are misread, ill-advised ultimatums are made, offenses are taken, and history happens. It is therefore no certainty that the current structure of the Eurozone will survive the next decade. The COVID-19 crisis has shown that some cracks were deeper than previous believed and accelerated the impact of long-term structural issues. It is no longer crazy to believe that the Euro might fail.

Central to any contemplation of the future of the Euro is the concept of Optimum Currency Areas discussed above. Whether the Euro or any successor currency can succeed is dependent upon 1) integration and mobility of labor, 2) price, wage and capital flexibility, 3) centralized budgeting to redistribute wealth to parts of the area which suffer due to labor and capital mobility, and 4) similar business cycles throughout the zone. The first two are basically satisfied through the EU and Customs Union. The third is somewhat satisfied by the EU. But the fourth requirement leads to much debate regarding how much the members’ national economies must move in harmony with each other.

With this in mind, and considering current and future economic, political, and social conditions in the various European nations, some potential paths are worthy of discussion. Of course, there are variations and complications with all potential paths, including these; but discussing multiple options before they evolve will allow smoother resolution of the complications.

Status Quo

When imaging how things might be in the future, it is easiest to revert to a future version of the current. This, however, rarely occurs, as evolution and events pull the course away from the narrow range of “likely” towards somewhere on the very wide range of “possible.” But let’s assume that this time is different, and the Euro continues in its current form without any substantial change in mandate or course alterations since that is close to what most stakeholders would prefer. Specifically, the frugal nations are likely operating under the assumption that southern nations will accept the best relief package they can get and, after a period of hard feelings, eventually return to business as usual. And that assumption might be correct.

However, as all European institutions have since the European Coal and Steel Commission in 1952, the ECB is likely to expand and integrate further. All EU members except Denmark are technically obligated to adopt the Euro at some point, with Bulgaria and Croatia already taking the necessary step of joining the Exchange Rate Mechanism (“ERM”). The other nations that “must” at some point join the Euro are Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden.

Viewed through the Optimum Currency Area lens, the expansion of the Eurozone will stretch the requirements of budgeting/redistribution and common business cycles. Since the Euro’s introduction, experts including monetary theorists, political scientists, and econometricians have weighed in on whether the Eurozone is an Optimum Currency Area. The idea of breaking it up, however, has never been seriously discussed because all members are relatively affluent and have integrated financial systems. It may, however, be challenging to sell the notion that the business cycles and financial systems in Sofia, Strasburg, Lodz, and Lisbon operate in harmony. And if the nineteen current Eurozone economies are finding it challenging to redistribute capital to nations that are lagging now, adding seven new members that are net recipients from the EU compared to only one net EU contributor may prove impossible.

Unfortunately for the frugal members that currently exert great sway in the ECB, the potential new members are much more like the southern Euro members, with Sweden an exception. Thus, the frugal nations would be wise to ensure any long-term division in the ECB falls along the lines of original vs. new member instead of frugal vs. everyone else. This will require them to give a little to their current ECB partners, with the Spanish proposal of spending through the EU budget currently the most palatable plan on the table. Otherwise the status quo, which is a state of perpetual expansion of European institutions, will cause the frugal nations much more heartburn in the future by causing the same issues to arise during the next global financial crisis, only with more partners seeking financial support.

Italy and Greece Leave Euro

Matteo Salvini will likely be the next Prime Minister of Italy as the head of the Lega party, supported by coalition partners Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. Lega and Fratelli d’Italia have been vocal in their Euroscepticism, and while Forza Italia is very pro-EU and Euro, Berlusconi tries to stay relevant any way he can, so he would join with these parties in the hope that issues with other European nations would blow over.

The coalition would know that it could not just leave the Euro, but would feel immense pressure to both stand up to what Italians view as northern European callousness and inject some life into the economy hardest hit by COVID-19. Living up to its political promises could cause it to take drastic action: reintroducing the Lira as a parallel currency for domestic transaction. To give those who spend money in Italy (specifically Italian businesses) an advantage, it would likely peg the value of the Lira (or a certain number of lira) at something like .95 Euro per Lira. Employers would seek to pay wages in the cheaper currency, but debts would still be owed in Euros. The ECB would almost certainly refuse to recognize the Lira and prohibit banks in the Eurozone from accepting it as payment even though its value would be pegged to the Euro. Italian leaders could argue that, unless it is expelled from the Eurozone after being declared a member state in derogation, its membership and full participation cannot be hindered; but the rest of the Eurozone members would be in no mood for legalities and do what they could to punish Italian behavior. Eventually, tensions would escalate with Italy halting payments to the ECB, and the ECB suspending Italy from its bond-purchasing program.

Such a move would be bad for the Eurozone, but catastrophic for Italy. The COVID-19 crisis has shown its leaders that fellow Europeans do not believe the nation to be so systemic as to require significant financial support in an emergency. With no support coming, Italian banks would face a double mismatch problem of liabilities short-term in Euros and assets long-term in Lira. The economy would need a lot of Euros cycling through it, but Italy’s trade to GDP ratio is only around 60%, which places it dead last in the EU, meaning banks would burn through their Euros quickly. Banka D’Italia would do everything it could to keep Euros in the system, defend the Lira to Euro peg, and keep the spread on Italian bonds manageable, but it would eventually burn through what reserves it possesses outside of those dedicated to the ECB (including nearly €90B in gold) and need to allow the currency to float. With this action, Italians would lose a significant portion of savings not held in Euros, and the economy would deteriorate even further.

There could be a silver lining in this scenario, however. Italy could decide to try to take advantage of the crisis to shed its debt and become more competitive. It could agree to expulsion from the Eurozone and fully transition to the Lira. Its populist government might then seek to redenominate its debt at the new depreciated exchange rate. Much like Argentina in 2005, Italy would likely offer to swap outstanding bonds for either a bond with a discount rate of around 60% of face value to mature at its original maturity date, or a longer-term bond at 100% value with smaller coupon payments.

Since it would be burning investors and would pay a large premium to access capital markets, Italy would need to be aggressive in creating growth. To do so, it could rely on a key membership it would not shed: the European Customs Union. With its cheaper yet well-educated workforce, complete access to the European market, and a willingness to provide special incentives to boost employment, Italy would be primed to attract employers looking to operate in the EU at lower costs than those in Eurozone countries. The economic warfare between Italy and the Eurozone would be vicious, but at least Italy could provide its citizens some hope.

Similarly, Italians and other Europeans refuse to listen to northern European lectures on public debt when those nations’ tax structures greatly contribute to the southern nations’ need to take on debt. The Netherlands, Luxembourg, and Ireland, with a combined 4.4% of the EU’s population, house more than 50% of global foreign direct investment. This is often in the form of holding companies to exploit the favorable tax regimes and corporate law in these three nations. Italian companies will domicile in the Netherlands and pay corporate taxes there while performing almost all operations in Italy. Even former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi has moved the “headquarters” of his Mediaset empire from Milan to Amsterdam. Thus, the tax haven nations receive the lower corporate taxes but need to provide virtually no services to the taxpayer, while the nations that must provide services to the employees of those taxpayers are left without the tax revenue they should have to provide them.

It is often challenging to measure the strength of these opinions, and even harder to determine how citizens would like to act upon the opinions if given the opportunity. Fortunately, Davide Angelucci and Vincenzo Emanuele recently conducted a detailed survey of Italian attitudes towards to EU for Centro Italiano Studi Electtorali. According to the survey, a shocking 85% believe the EU is not helping Italy in its fight against COVID-19. 42% of Italians have a negative opinion of the EU, 23% are neutral, and only 35% hold positive opinion of the EU. Additionally, 35% would like to leave the EU, 18% prefer to leave the Euro but not the EU, and 47% would choose to stay in the EU. Anti-EU sentiment in Italy is growing, and failure of the EU and ECB to support Italy in near future could push it out of the Euro.

Possible Outcomes

When considering how these divides might impact the Euro, it is important to begin any analysis with an understanding that *nobody* who would experience real consequences, financial or electoral, wants even a partial failure of the Euro. Of course, populist politicians like Matteo Salvini rattle sabers because 65% of the voters for his Lega party would like to leave the EU; but the financial and industrial giants in Lega’s northern Italian strongholds would certainly do all they could to kill any Italeave movement. So there is a strong desire to patch over any differences and retain the status quo. But disagreements occur, intentions are misread, ill-advised ultimatums are made, offenses are taken, and history happens. It is therefore no certainty that the current structure of the Eurozone will survive the next decade. The COVID-19 crisis has shown that some cracks were deeper than previous believed and accelerated the impact of long-term structural issues. It is no longer crazy to believe that the Euro might fail.

Central to any contemplation of the future of the Euro is the concept of Optimum Currency Areas discussed above. Whether the Euro or any successor currency can succeed is dependent upon 1) integration and mobility of labor, 2) price, wage and capital flexibility, 3) centralized budgeting to redistribute wealth to parts of the area which suffer due to labor and capital mobility, and 4) similar business cycles throughout the zone. The first two are basically satisfied through the EU and Customs Union. The third is somewhat satisfied by the EU. But the fourth requirement leads to much debate regarding how much the members’ national economies must move in harmony with each other.

With this in mind, and considering current and future economic, political, and social conditions in the various European nations, some potential paths are worthy of discussion. Of course, there are variations and complications with all potential paths, including these; but discussing multiple options before they evolve will allow smoother resolution of the complications.

Status Quo

When imaging how things might be in the future, it is easiest to revert to a future version of the current. This, however, rarely occurs, as evolution and events pull the course away from the narrow range of “likely” towards somewhere on the very wide range of “possible.” But let’s assume that this time is different, and the Euro continues in its current form without any substantial change in mandate or course alterations since that is close to what most stakeholders would prefer. Specifically, the frugal nations are likely operating under the assumption that southern nations will accept the best relief package they can get and, after a period of hard feelings, eventually return to business as usual. And that assumption might be correct.

However, as all European institutions have since the European Coal and Steel Commission in 1952, the ECB is likely to expand and integrate further. All EU members except Denmark are technically obligated to adopt the Euro at some point, with Bulgaria and Croatia already taking the necessary step of joining the Exchange Rate Mechanism (“ERM”). The other nations that “must” at some point join the Euro are Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Sweden.

Viewed through the Optimum Currency Area lens, the expansion of the Eurozone will stretch the requirements of budgeting/redistribution and common business cycles. Since the Euro’s introduction, experts including monetary theorists, political scientists, and econometricians have weighed in on whether the Eurozone is an Optimum Currency Area. The idea of breaking it up, however, has never been seriously discussed because all members are relatively affluent and have integrated financial systems. It may, however, be challenging to sell the notion that the business cycles and financial systems in Sofia, Strasburg, Lodz, and Lisbon operate in harmony. And if the nineteen current Eurozone economies are finding it challenging to redistribute capital to nations that are lagging now, adding seven new members that are net recipients from the EU compared to only one net EU contributor may prove impossible.

Unfortunately for the frugal members that currently exert great sway in the ECB, the potential new members are much more like the southern Euro members, with Sweden an exception. Thus, the frugal nations would be wise to ensure any long-term division in the ECB falls along the lines of original vs. new member instead of frugal vs. everyone else. This will require them to give a little to their current ECB partners, with the Spanish proposal of spending through the EU budget currently the most palatable plan on the table. Otherwise the status quo, which is a state of perpetual expansion of European institutions, will cause the frugal nations much more heartburn in the future by causing the same issues to arise during the next global financial crisis, only with more partners seeking financial support.

Italy and Greece Leave Euro

Matteo Salvini will likely be the next Prime Minister of Italy as the head of the Lega party, supported by coalition partners Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy) and former Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia. Lega and Fratelli d’Italia have been vocal in their Euroscepticism, and while Forza Italia is very pro-EU and Euro, Berlusconi tries to stay relevant any way he can, so he would join with these parties in the hope that issues with other European nations would blow over.

The coalition would know that it could not just leave the Euro, but would feel immense pressure to both stand up to what Italians view as northern European callousness and inject some life into the economy hardest hit by COVID-19. Living up to its political promises could cause it to take drastic action: reintroducing the Lira as a parallel currency for domestic transaction. To give those who spend money in Italy (specifically Italian businesses) an advantage, it would likely peg the value of the Lira (or a certain number of lira) at something like .95 Euro per Lira. Employers would seek to pay wages in the cheaper currency, but debts would still be owed in Euros. The ECB would almost certainly refuse to recognize the Lira and prohibit banks in the Eurozone from accepting it as payment even though its value would be pegged to the Euro. Italian leaders could argue that, unless it is expelled from the Eurozone after being declared a member state in derogation, its membership and full participation cannot be hindered; but the rest of the Eurozone members would be in no mood for legalities and do what they could to punish Italian behavior. Eventually, tensions would escalate with Italy halting payments to the ECB, and the ECB suspending Italy from its bond-purchasing program.

Such a move would be bad for the Eurozone, but catastrophic for Italy. The COVID-19 crisis has shown its leaders that fellow Europeans do not believe the nation to be so systemic as to require significant financial support in an emergency. With no support coming, Italian banks would face a double mismatch problem of liabilities short-term in Euros and assets long-term in Lira. The economy would need a lot of Euros cycling through it, but Italy’s trade to GDP ratio is only around 60%, which places it dead last in the EU, meaning banks would burn through their Euros quickly. Banka D’Italia would do everything it could to keep Euros in the system, defend the Lira to Euro peg, and keep the spread on Italian bonds manageable, but it would eventually burn through what reserves it possesses outside of those dedicated to the ECB (including nearly €90B in gold) and need to allow the currency to float. With this action, Italians would lose a significant portion of savings not held in Euros, and the economy would deteriorate even further.

There could be a silver lining in this scenario, however. Italy could decide to try to take advantage of the crisis to shed its debt and become more competitive. It could agree to expulsion from the Eurozone and fully transition to the Lira. Its populist government might then seek to redenominate its debt at the new depreciated exchange rate. Much like Argentina in 2005, Italy would likely offer to swap outstanding bonds for either a bond with a discount rate of around 60% of face value to mature at its original maturity date, or a longer-term bond at 100% value with smaller coupon payments.

Since it would be burning investors and would pay a large premium to access capital markets, Italy would need to be aggressive in creating growth. To do so, it could rely on a key membership it would not shed: the European Customs Union. With its cheaper yet well-educated workforce, complete access to the European market, and a willingness to provide special incentives to boost employment, Italy would be primed to attract employers looking to operate in the EU at lower costs than those in Eurozone countries. The economic warfare between Italy and the Eurozone would be vicious, but at least Italy could provide its citizens some hope.

The battle between Italy and the rest of the Eurozone would not go unnoticed in the nations that “must” join the Euro, and they would probably be hesitant to enter into a monetary union that cannot be undone without economic warfare. Simultaneously, Greece would feel like even more of an outlier in the Eurozone and realize that it is a populist government away from enduring the same fate as Italy. Eurozone leaders could use this as an opportunity to show how a nation can leave the Euro on friendly terms. The parties would both be happy to negotiate a Grexit through which the ECB supports Greece’s transition back to the Drachma and keeps its debts payable in Euros. The Drachma is tied to the Euro, and the ECB would agree to provide a certain level of capital to defend that peg for several years.

Regional Euros, With or Without Italy and Greece

Regardless of whether Italy and Greece leave the Euro, COVID-19 is exposing existential deep divides between Eurozone nations that will not be easily overcome. Two camps of nations led by Germany and France fundamentally disagree on the role of the ECB and integration. Additionally, if Italy leaves and redenominates its debt, the redenomination risk priced into the bonds of nations like Spain and Portugal would skyrocket. The spread between bonds in the Eurozone could become much too expensive for the ECB to manage. Risk would need to be localized instead of socialized, and the only way to effectively do this would be to break the Eurozone into Euro regions under the auspices of the ECB: essentially live in the same neighborhood but not the same house.

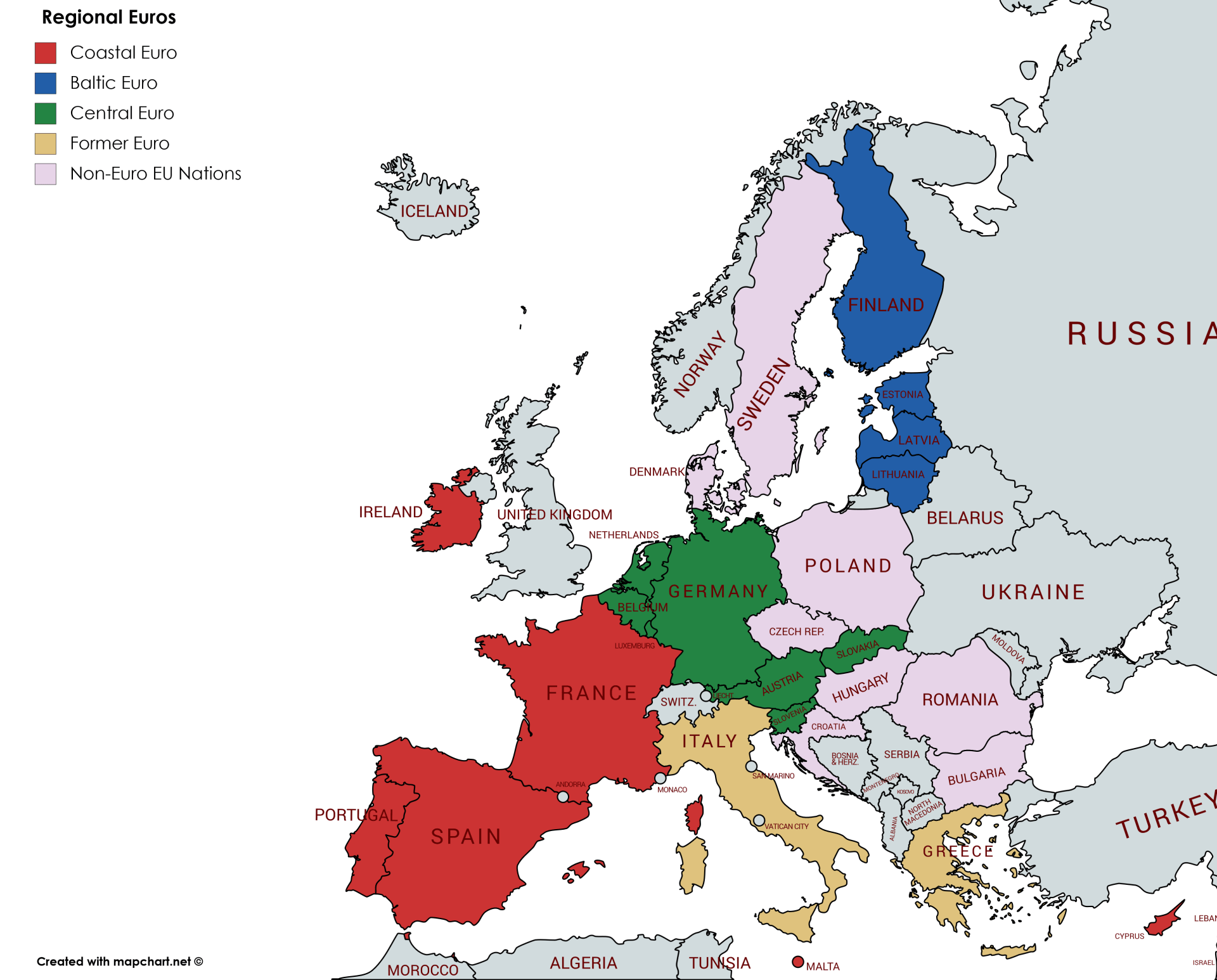

Breaking the Eurozone into three smaller but closely regulated monetary regions under the auspices of the ECB would both stabilize the nations’ monetary policy through more regionally-appropriate methods and contain any events that arise within those areas. They would be designed to take advantage of the attributes that make them Optimum Currency Areas, and cultural ties would facilitate easier resolution of issues.

Baltic Euro

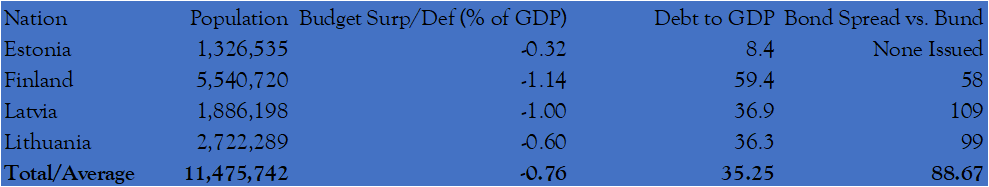

The first region, the Baltic Euro, is by far the smallest. It would consist of Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia and would be relatively stable as fiscal policy has always been conservative in these nations. Further, if any unforeseen issues arise in this region, assistance from the other regions will be very effective given the small size of aid that would be needed to resolve a crisis.

Breaking the Eurozone into three smaller but closely regulated monetary regions under the auspices of the ECB would both stabilize the nations’ monetary policy through more regionally-appropriate methods and contain any events that arise within those areas. They would be designed to take advantage of the attributes that make them Optimum Currency Areas, and cultural ties would facilitate easier resolution of issues.

Baltic Euro

The first region, the Baltic Euro, is by far the smallest. It would consist of Finland, Estonia, Lithuania, and Latvia and would be relatively stable as fiscal policy has always been conservative in these nations. Further, if any unforeseen issues arise in this region, assistance from the other regions will be very effective given the small size of aid that would be needed to resolve a crisis.

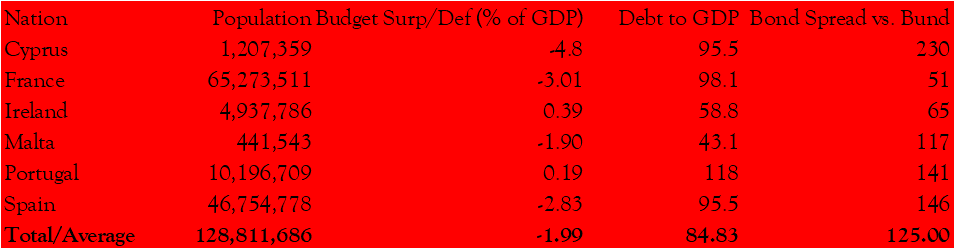

Coastal Euro

The next region is the most diverse and potentially most volatile; but share a vision of European unity and fiscal cooperation. France, Spain, Portugal, Malta, Cyprus, and Ireland work incredibly well together, and have made the political commitments necessary to defend each-others’ ability to borrow. They would likely even issue joint bonds to obtain the benefits of pooled risk. They are happy to work with the Germans through the ECB, but are also happy to determine the region’s monetary policy in a more democratic manner.

The next region is the most diverse and potentially most volatile; but share a vision of European unity and fiscal cooperation. France, Spain, Portugal, Malta, Cyprus, and Ireland work incredibly well together, and have made the political commitments necessary to defend each-others’ ability to borrow. They would likely even issue joint bonds to obtain the benefits of pooled risk. They are happy to work with the Germans through the ECB, but are also happy to determine the region’s monetary policy in a more democratic manner.

If Italy and Greece were to remain in the Euro, this is the region they would join, which would skew all of the chart’s numbers towards more debt and higher bond spreads. These nations have worked well together in the EU and ECB, so it is fair to assume they would continue to cooperate through this regional Euro.

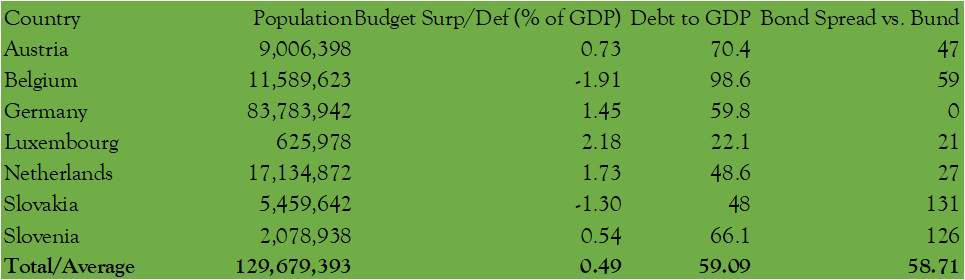

Central Euro

The final region is the Central Euro, consisting of Germany, Austria, the Slovak Republic, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Slovenia. Belgium’s fiscal policy fits more comfortably with the previous region, but the investments in and deep connections to the Benelux ideal draws it into this one. Germany and the Netherlands make most decisions in this region; but unlike the entire Eurozone before the breakup, their partners are happy to defer since they greatly benefit from their monetary association with Germany. Sovereign bond spreads between the nations would decline significantly, and the members would be more likely to assist each other in an emergency since they share values and a history of fiscal prudence.

Central Euro

The final region is the Central Euro, consisting of Germany, Austria, the Slovak Republic, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Slovenia. Belgium’s fiscal policy fits more comfortably with the previous region, but the investments in and deep connections to the Benelux ideal draws it into this one. Germany and the Netherlands make most decisions in this region; but unlike the entire Eurozone before the breakup, their partners are happy to defer since they greatly benefit from their monetary association with Germany. Sovereign bond spreads between the nations would decline significantly, and the members would be more likely to assist each other in an emergency since they share values and a history of fiscal prudence.

Coordination

The Euro and non-Euro EU nations would coordinate their exchange rates through an enhanced European Exchange Rate Mechanism (the ERM). Hard feelings would likely exist on all sides; but like divorced couples with common debts, it would be best to work together on a limited basis instead of refighting old battles that do not benefit anyone. Additionally, all nations would remain members of the EU and Customs Union, so there are ample opportunities to work together on continent-wide issues and engage in initiatives between the Euro regions.

The COVID-19 crisis has forced Europeans to reevaluate what it means to be both their nationalities and European, and exposed their fellow Europeans’ beliefs on that issue. As a result, they have learned that old prejudices linger and, in many cases, national well-being trumps continental recovery. Such revelations make the fractures in the Eurozone difficult to mend, and make the unthinkable – the end of the Euro – slightly more possible. The issues exposed by the COVID-19 crisis will not disappear, and will almost certainly arise again at a most unfortunate time if not properly addressed now. Thus, it would behoove leaders on all sides of the debate to honestly confront the Eurozone’s structural problems before the promise of Europe fades away.

The Euro and non-Euro EU nations would coordinate their exchange rates through an enhanced European Exchange Rate Mechanism (the ERM). Hard feelings would likely exist on all sides; but like divorced couples with common debts, it would be best to work together on a limited basis instead of refighting old battles that do not benefit anyone. Additionally, all nations would remain members of the EU and Customs Union, so there are ample opportunities to work together on continent-wide issues and engage in initiatives between the Euro regions.

Hard Choices Ahead

The COVID-19 crisis has forced Europeans to reevaluate what it means to be both their nationalities and European, and exposed their fellow Europeans’ beliefs on that issue. As a result, they have learned that old prejudices linger and, in many cases, national well-being trumps continental recovery. Such revelations make the fractures in the Eurozone difficult to mend, and make the unthinkable – the end of the Euro – slightly more possible. The issues exposed by the COVID-19 crisis will not disappear, and will almost certainly arise again at a most unfortunate time if not properly addressed now. Thus, it would behoove leaders on all sides of the debate to honestly confront the Eurozone’s structural problems before the promise of Europe fades away.